About this work: I worked on this mech-interp research last summer with Andy Arditi (currently at the very cool David Bau lab at Northeastern) as part of the winter 2025 cohort of SPAR. This is a focused case study on DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Llama-8B, and not a sweeping global investigation, but it does suggest that models might treat reasoning as a totally distinct mode of text output. I find this reasoning mode transition fascinating and think it deserves more research, which I intend to pursue. In the meantime, though, I thought I’d share the current draft of the work here.

Abstract

Reasoning models segregate generations into “reasoning” and “answering” regions, but the mechanism that toggles between these modes is unclear. We study DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Llama-8B and show that residual-stream activations for tokens in the two regions are linearly separable across many layers. A simple difference-in-means direction isolates a layerwise shift that flips sign sharply at the reasoning-answering boundary, indicating an abrupt mode transition. While this geometry suggests a potential control handle, we did not find a clean ‘on–off’ switch (e.g., a single head or single-layer direction) that robustly toggles the mode across prompts; however we did find that both single and multi-layer interventions can qualitatively steer the model towards reasoning or answering behavior.

Introduction

Reasoning models have proven highly successful by incorporating regions of deliberate extended reasoning into their generation process. Modern reasoning models usually segregate generations into dedicated “reasoning” and “answering” regions. The distribution of text generated within reasoning regions (which we refer to here as ‘reasoning mode’) tends to differ significantly from text in answering regions (‘answering mode’): reasoning mode exhibits exploratory, verbose patterns—most famously implementing backtracking by outputting tokens like “wait” to express uncertainty—while answering mode tends to produce direct, polished responses. This creates a bimodal form of text generation, and raises an interesting mechanistic question: how does the model represent and transition between these two modes?

We study DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Llama-8B and analyze residual-stream activations associated with reasoning versus answering tokens. We find that, across nearly all layers, the two modes are well-separated linearly by a difference-in-means direction, and that projections onto this direction flip sign sharply at the reasoning–answering boundary, indicating an abrupt transition. We then explore methods to control the shift: while the linear geometry suggests a potential handle, we did not identify a clean “on–off” switch (e.g., a single attention head or a single direction) that robustly toggles the mode across a diverse distribution of prompts; however, we do find that multi-layer interventions qualitatively appear to provide more consistent steering toward either mode.

Linear separability of reasoning and answering activations

The transformer residual stream is the shared communication channel read and written by attention and MLP components. A growing body of work shows that features in this space are represented as linear directions, and can often be recovered with simple methods such as sparse autoencoders or linear probes. Moreover, editing residual activations along these feature directions can steer model behavior. Motivated by this, we analyze residual stream activations of tokens produced in reasoning mode versus answering mode to characterize the geometric shift between them.

Data collection

We sample 100 prompts from GSM8K and 100 prompts from each of several MMLU subject splits. For each prompt, we sample a single rollout at temperature 1. We cap generations at 500 tokens for GSM8K and 1025 for MMLU. Generations follow the template:

<|User|>[MESSAGE]<|Assistant|><think>\n[REASONING TOKENS]\n</think>\n\n[ANSWERING TOKENS]<EOS>

We label tokens as reasoning or answering by membership in the [REASONING TOKENS] or [ANSWERING TOKENS] regions, respectively. For each labeled token, we extract the post-MLP residual stream activation at every layer $l\in{0,\dots,L-1}$, denoting the activation for token $t$ by $\mathbf{h}^{l}{t}$. This yields two datasets per layer: $\mathcal{D}{\text{reas.}}^{l}$, consisting of all reasoning token activations, and $\mathcal{D}_{\text{ans.}}^{l}$, consisting of all answering token activation.

Difference-in-means analysis

To characterize the difference between the two datasets, we compute the difference-in-means. For each layer $l$, we first compute the per-class means:

\[\mu_{\text{reas.}}^{l} = \frac{1}{|\mathcal{D}_{\text{reas.}}^{l}|} \sum_{\mathbf{h}^{l}_{t}\in \mathcal{D}_{\text{reas.}}^{l}} \mathbf{h}^{l}_{t},\quad \mu_{\text{ans.}}^{l} = \frac{1}{|\mathcal{D}_{\text{ans.}}^{l}|} \sum_{\mathbf{h}^{l}_{t}\in \mathcal{D}_{\text{ans.}}^{l}} \mathbf{h}^{l}_{t}.\]As a convention, we define the difference vector, $\delta^l = \mu_{\text{ans.}}^{l} - \mu_{\text{reas.}}^{l}$, to point from reasoning mode towards answering mode. We thus refer to it as the answering mode vector.

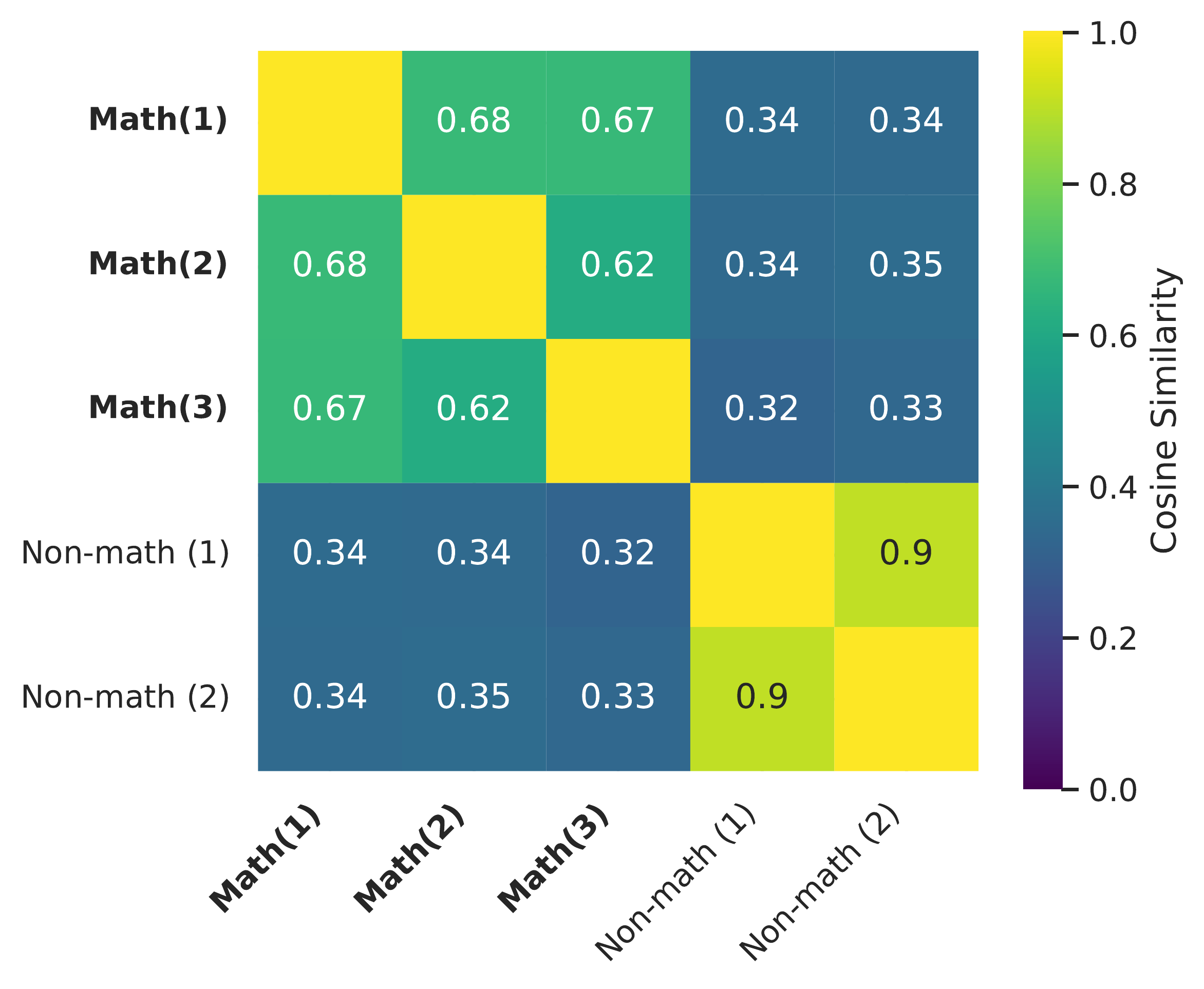

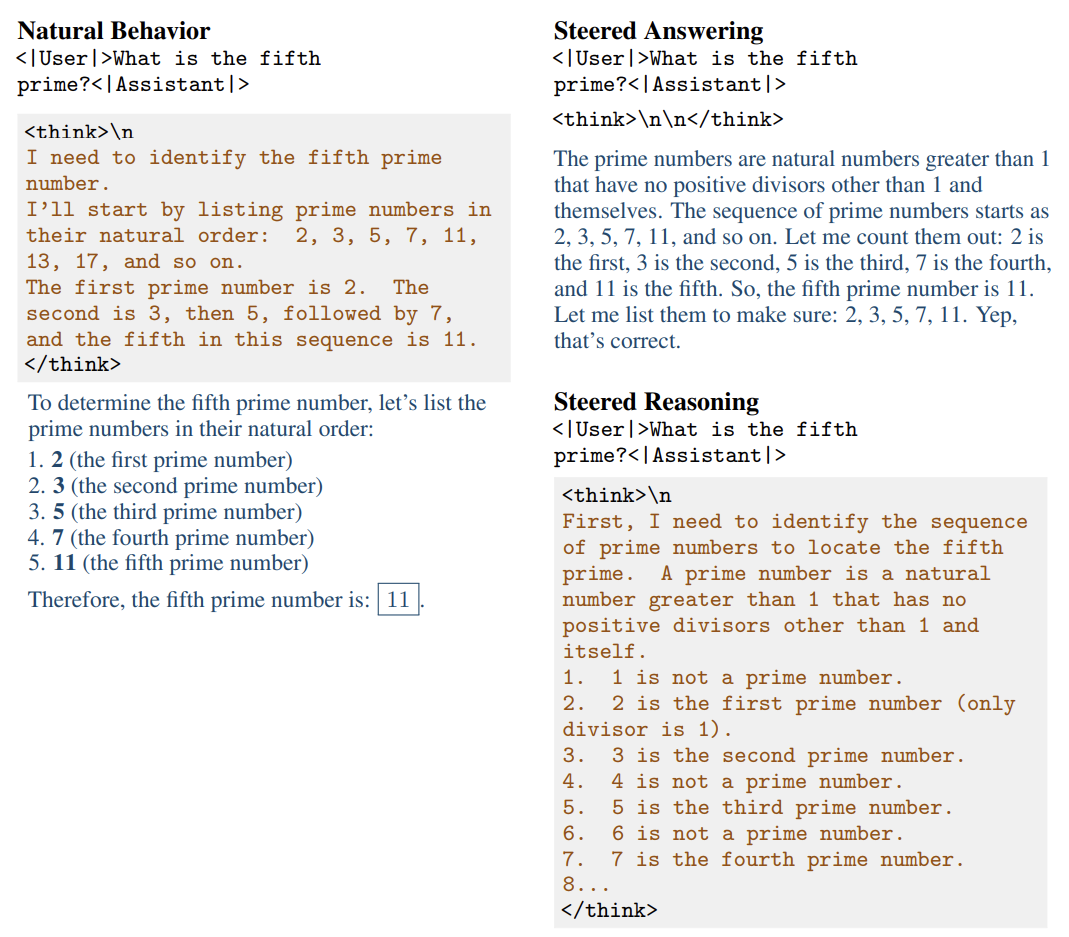

The answering mode vector differs across domains. We compute a difference vector for each dataset split separately. Interestingly, we find that the difference vectors are not well aligned between different mathematical and non-mathematical domains. The figure above shows that math splits form a similar block, while other non-math subjects form a distinct block (see also the appendix). This domain-specific divergence is notable, and we do not currently understand its underlying cause.

For all subsequent results, we narrow our domain to only consider math splits (GSM8K, MMLU Abstract Algebra, MMLU College Mathematics).

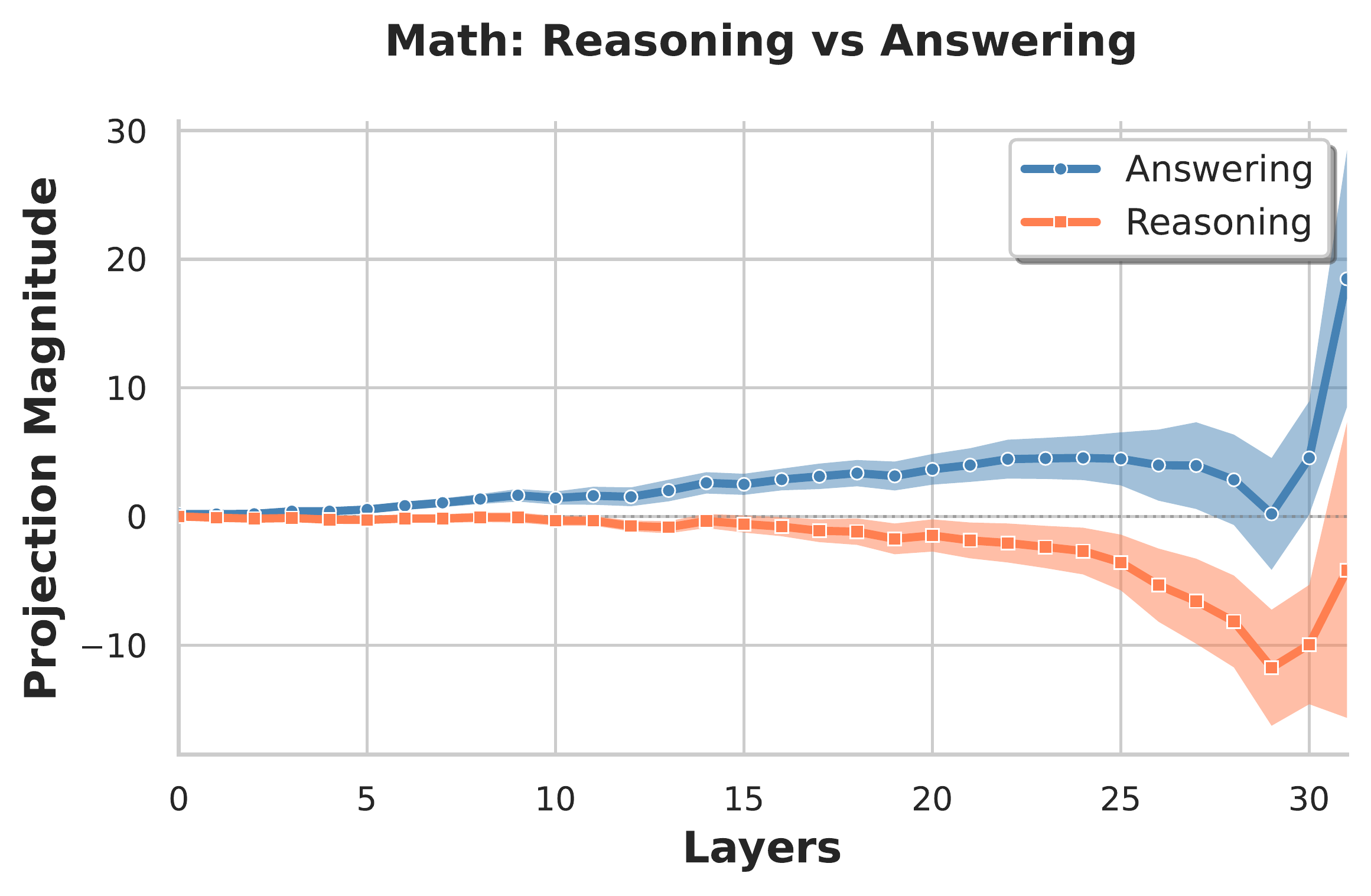

Layerwise magnitude and alignment. Starting around layer 5, there emerges a clear separation between reasoning and answering activations, a gap that grows as layer increases (figure below, left).

We verify that the linear separability of the residual stream is not simply an artifact of differences in token frequency between the reasoning and answering regions, as a token-normalized control (see appendix) yields similar trends.

We additionally observe that the difference directions sourced from adjacent layers are generally close, particularly later in the network (figure below, right). Note that the difference direction at the last layer (layer 31) is an exception, and is quite different from subsequent directions. This is not surprising, as the final post-MLP residual stream vector feeds almost directly into the unembedding layer.

Boundary toggle at </think>. To visualize the mode switch, we align tokens by their offset $k$ relative to the closing </think> boundary and plot the projection

where $\hat{\delta}^{l} = \frac{\delta^{l}}{\lvert \lvert \delta^l \rvert \rvert_2}$.

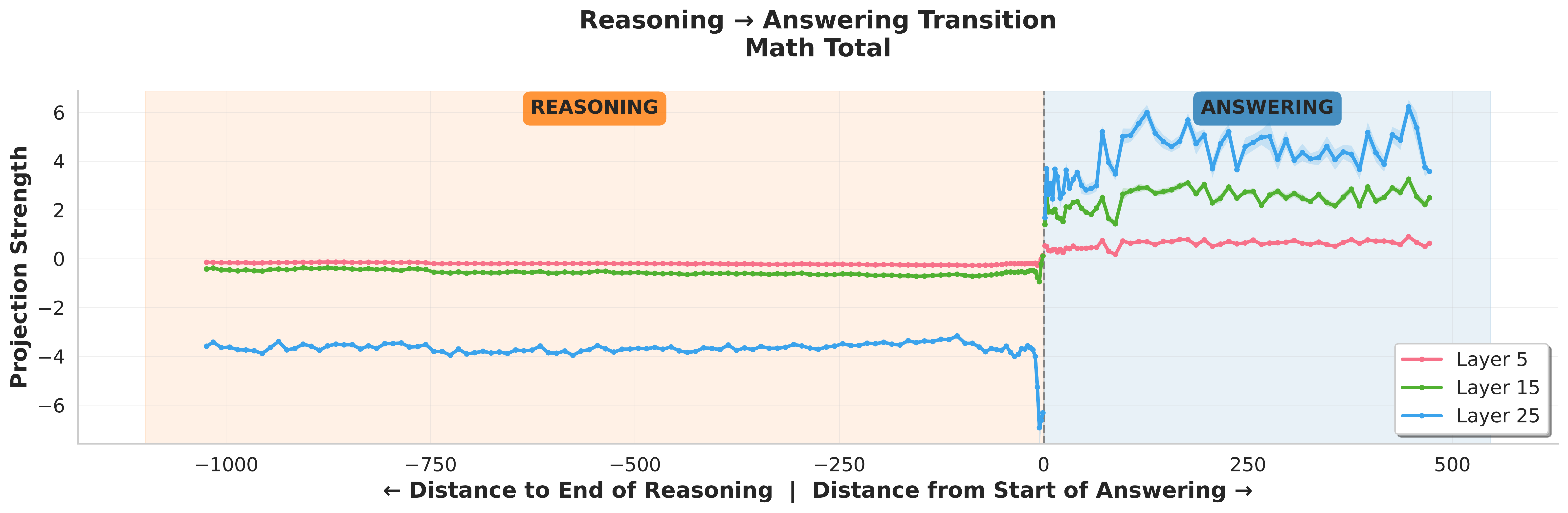

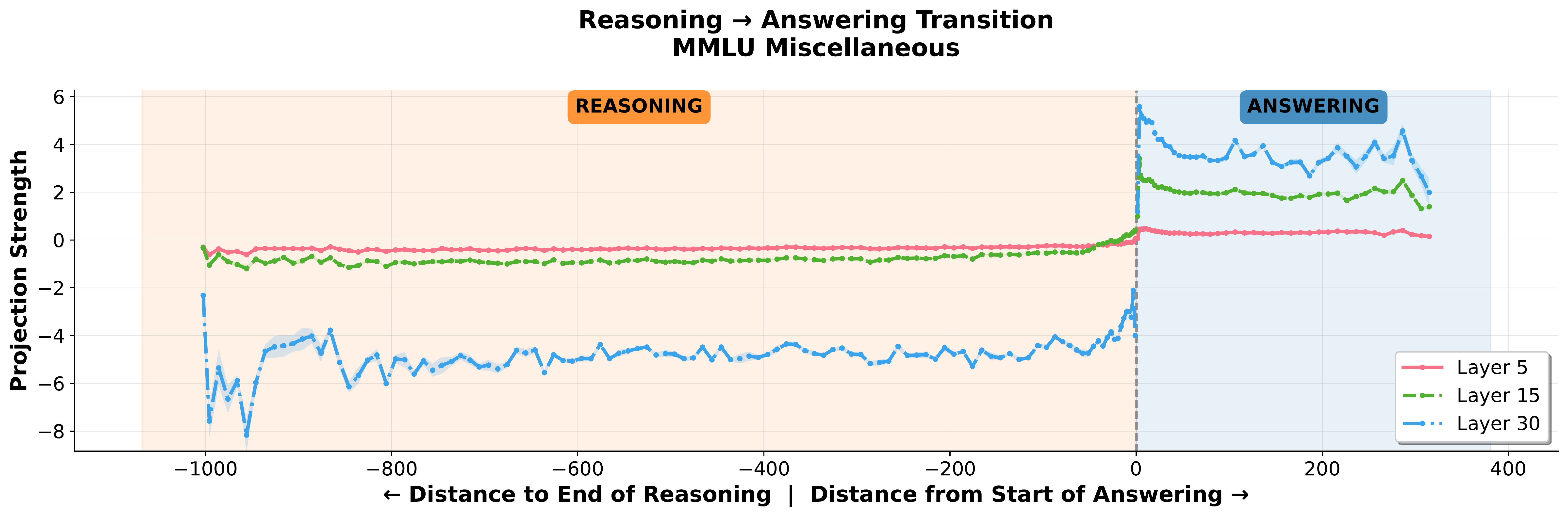

Averaging $p^{l}_{t}$ over examples reveals a sharp transition from negative (reasoning) to positive (answering) at $k=0$ (figure below). This directly demonstrates a linear shift in activation space corresponding to the reasoning→answering boundary, akin to a toggle switch.

</think> boundary. For $l\in\{ 5, 15,25\}$, we plot the average projection $p_t^{l}=\langle \mathbf{h}^{l}_{t},\hat{\delta}^{l}\rangle$ of token activations onto the unit difference-in-means direction as a function of token offset $k$ from the closing </think> tag (negative $k$: reasoning region; positive $k$: answering). The projection abruptly flips sign at $k{=}0$, corresponding precisely to the </think> boundary.Model steering

To understand the causality of these linear shifts, we run quantitative experiments targeting specific layers. While single-layer injection demonstrably biases the model towards the targeted mode, the effect has limited reliability. Although a systematic exploration of multi-layer interventions is beyond our scope, we find qualitatively that multi-layer interventions produce a much more reliable effect for inducing reasoning or answering mode behavior.

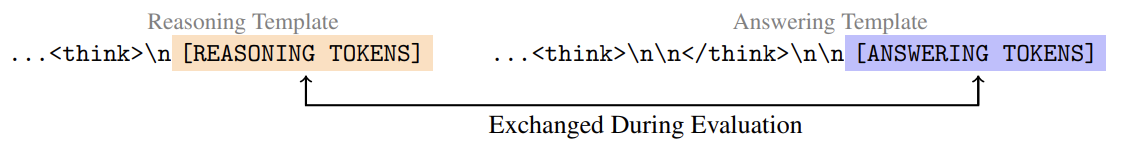

Successfully steering the model would mean that an intervention shifts its probabilities so that it prefers tokens of one mode even when the surrounding context would normally elicit the other. To quantify this effect, we sample prompts from GSM-8K, MMLU College Mathematics, and MMLU Abstract Algebra (100 each, distinct from our difference-in-means analysis), swap reasoning and answering completions between contexts, and measure the degree to which steering closes the gap between their baseline and cross-context log-probabilities.

We use the standard prompt format to produce at most 100 reasoning tokens (ending at </think>). To generate at most 100 answering tokens, we exploit a noted behavior of DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Llama-8B, in which the model skips reasoning entirely (see appendix). This provides a prompt template to immediately elicit answers without first reasoning. After generating, we then swap the two completions into their opposite contexts.

Single-layer injections

For single-layer steering, we inject the normalized difference-in-means vector $\hat{\delta}^l$ (scaled by a coefficient) into the post-MLP residual stream at layer $l$. We use a negative coefficient to steer toward reasoning mode and a positive coefficient toward answering mode.

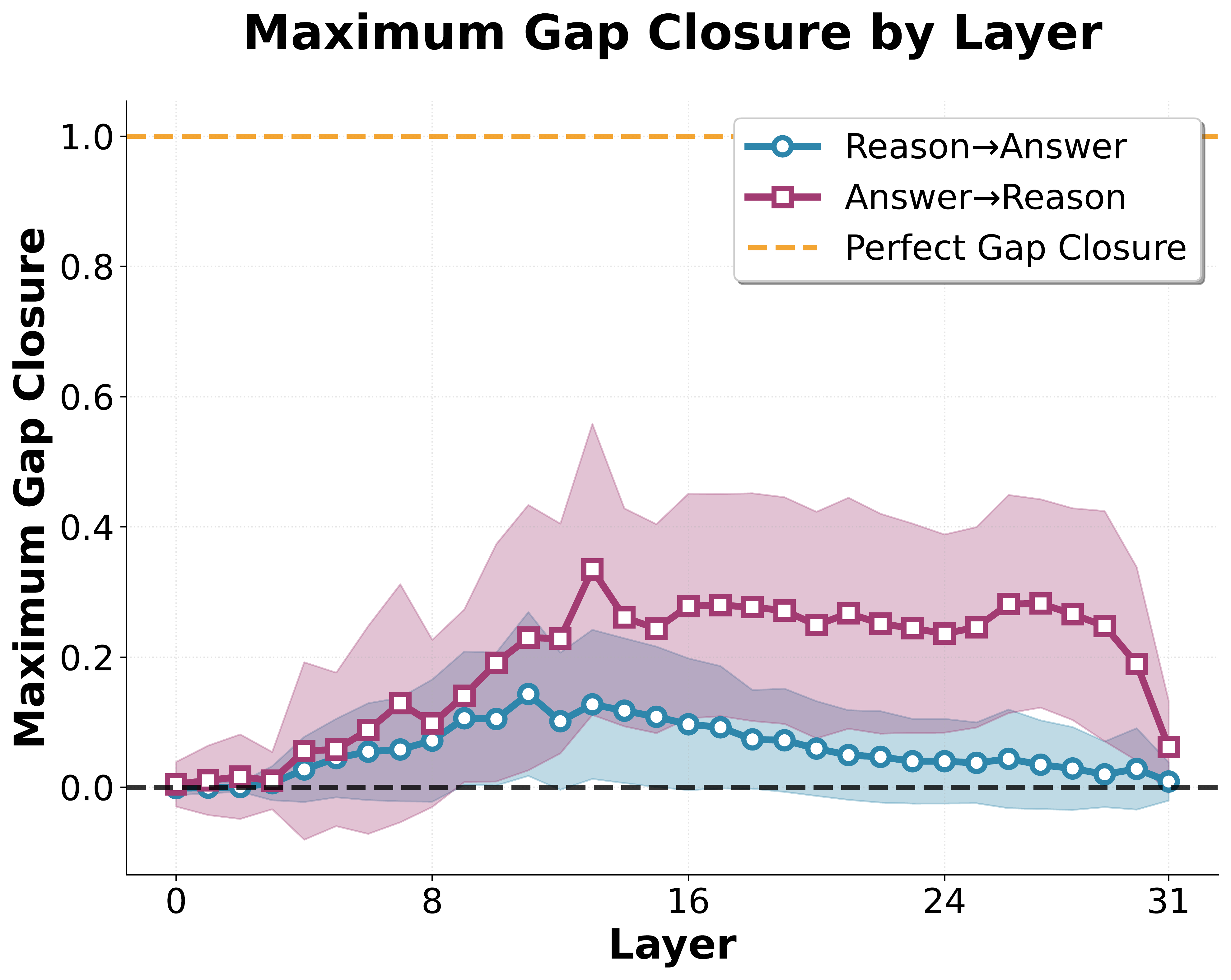

We sweep over a range of steering coefficients and measure the fraction of the log-probability gap closed for each prompt. For each layer, we identify the steering coefficient that maximizes the average gap closure across prompts and report this maximum value.

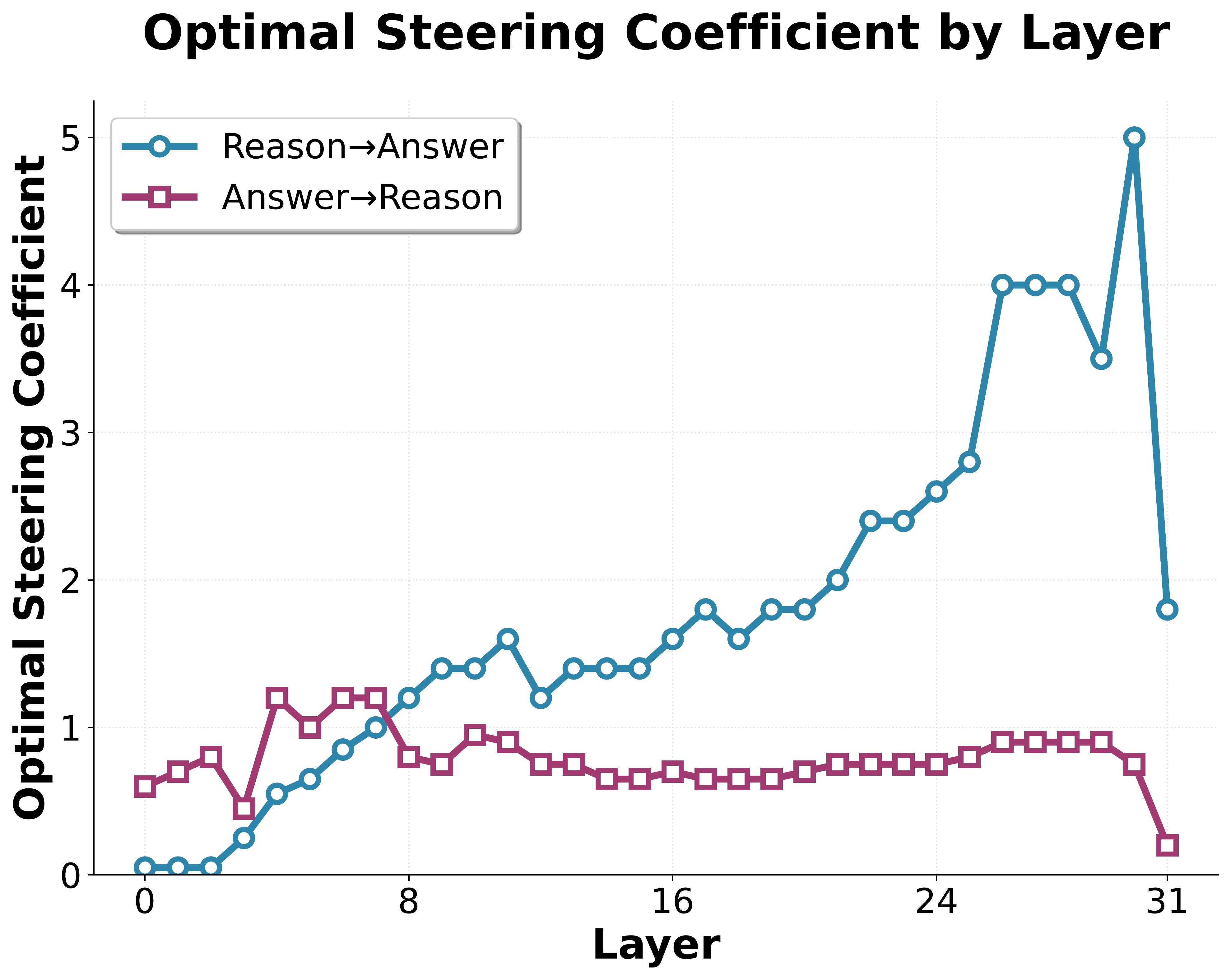

Results (shown above) suggest that while single-layer steering does increase the likelihood of the steered mode, the effect is not reliable across prompts. However, injecting at multiple layers gives reliable completions which qualitatively resemble the style of the targeted mode.

<think> tags and answering mode (bottom) with direct responses. Right: Steered behavior shows successful mode switching—Steered Answering (top) exhibits reasoning-like exposition despite being in answering mode, while Steered Reasoning (bottom) exhibits answering-like enumeration inside <think> tags. Steering was performed by injecting into layers 15 through 19, using a steering coefficient of +0.84 for Steered Reasoning, and −0.84 for Steered Answering.Discussion

We document a simple geometric signature of the reasoning–answering transition in DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Llama-8B: residual-stream activations are linearly separable across many layers, and projections onto a difference-in-means direction flip sign sharply at the boundary.

We then investigated whether this geometry yields a clean control mechanism. Under our experimental settings, we ultimately did not identify a single “on–off” switch—e.g., a single attention head or a single residual-stream direction—that reliably toggles the mode across prompts. However, our steering experiments demonstrate that the style and structure of the model’s outputs can be shifted demonstrably through targeted interventions, particularly when applied across multiple layers.

We additionally performed mechanistic analysis and found a critical attention head that appeared to cleanly toggle reasoning (see appendix). However, this result only held for the narrow distribution of short math prompts used in our initial investigation, and broke down when evaluating on a broader set of prompts.

More broadly, our results contribute to understanding how reasoning models internally represent and control their dual-mode generation process—a capability central to their effectiveness.

Appendix

Difference-in-means across subjects

Cosine-similarities

We sampled 100 prompts from a range of subjects from MMLU, as well as GSM-8K, and computed the subject-specific difference-in means. Using this, we computed the cosine-similarities across subjects. Interestingly, these subjects appear to separate based mostly on whether they are mathematical or not.

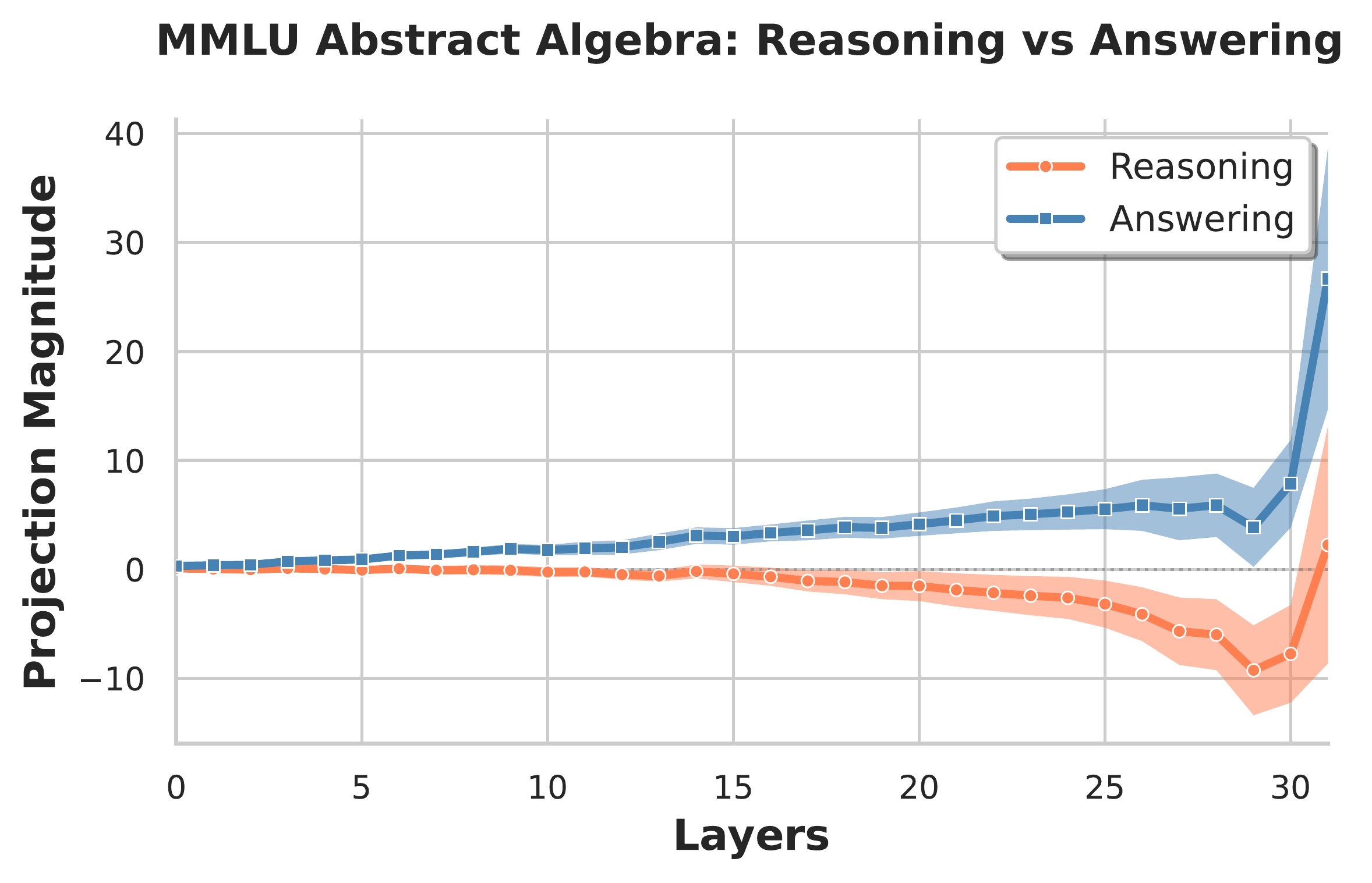

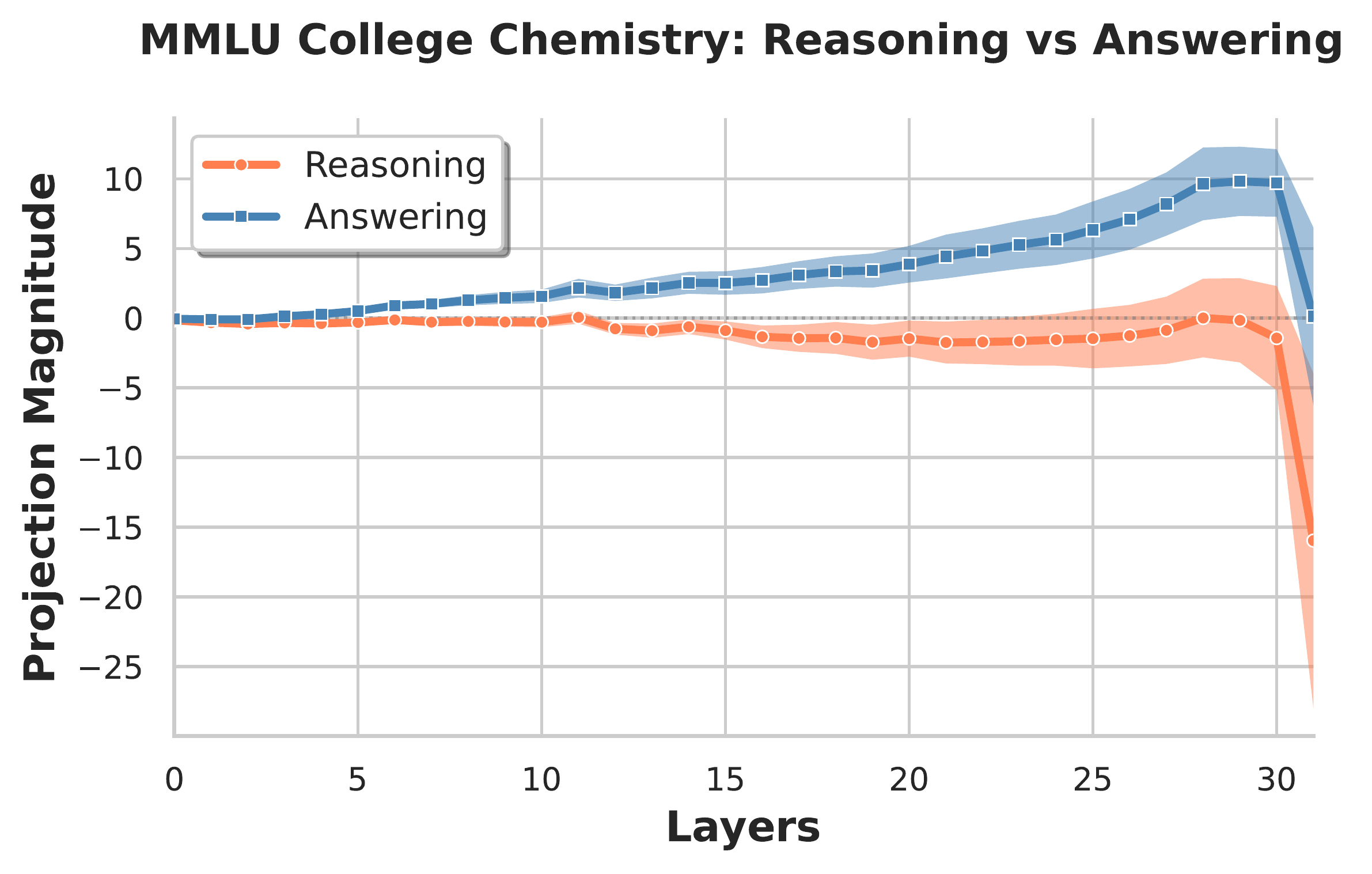

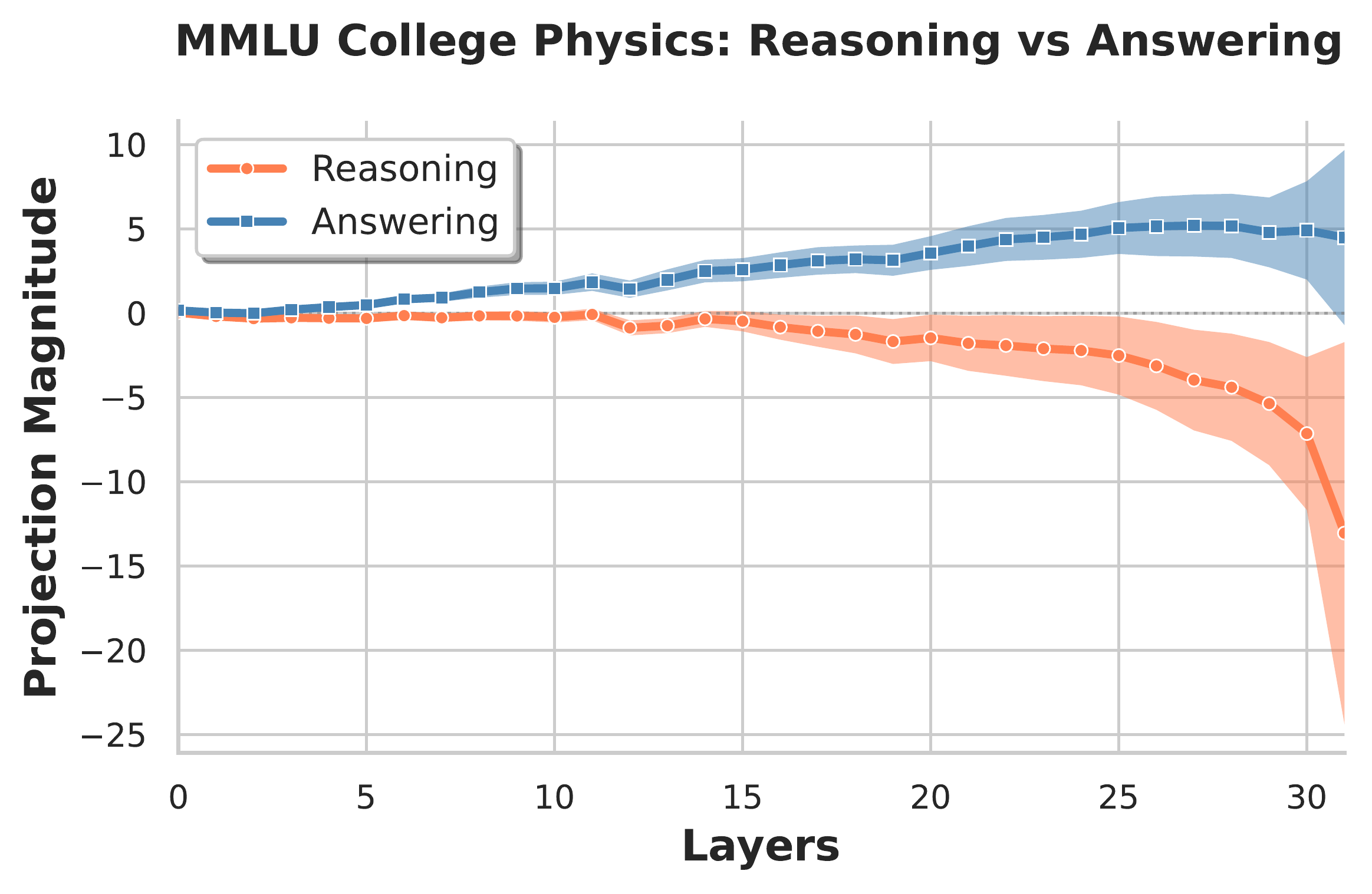

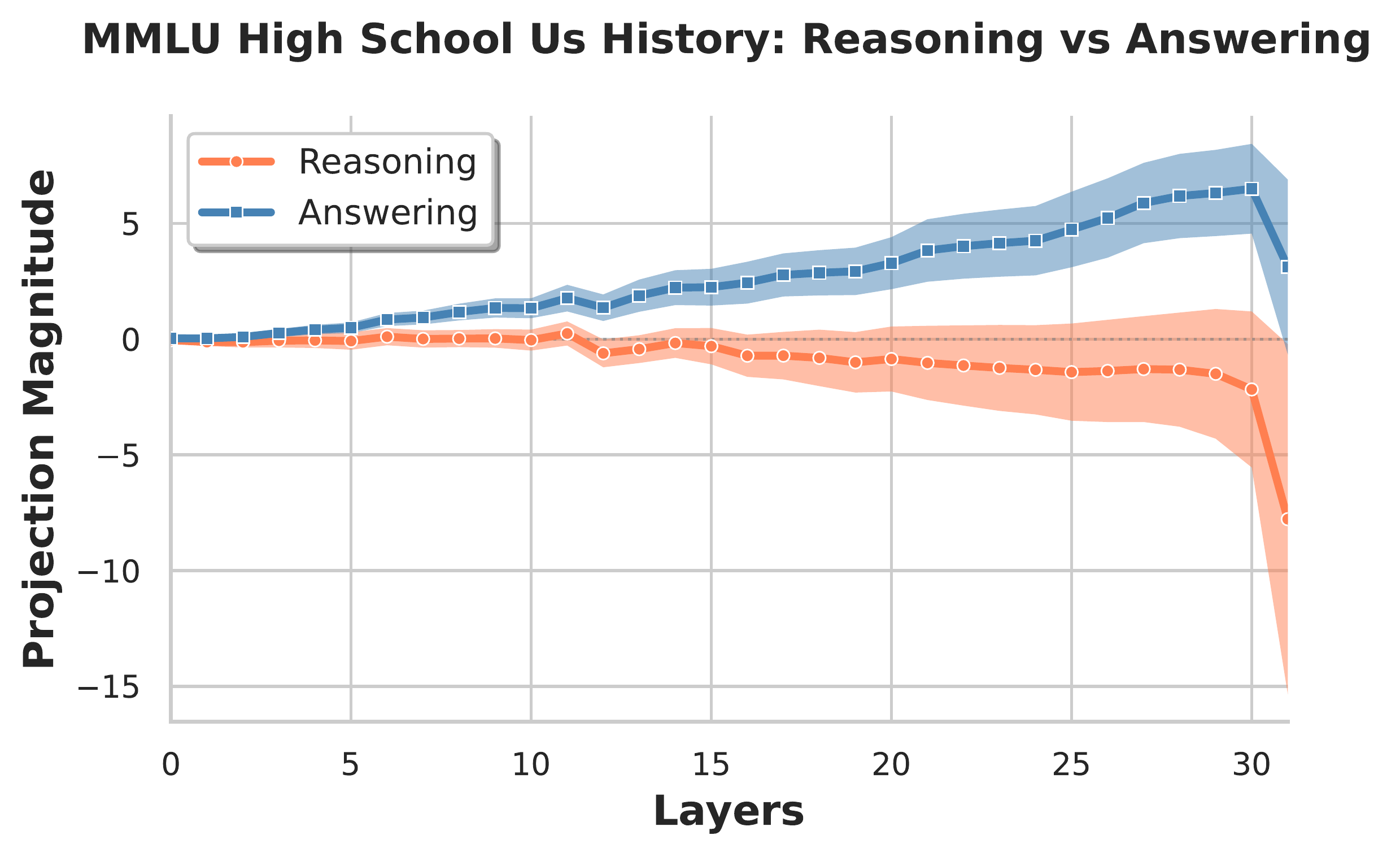

Reasoning-answering split

For all subjects, there exists a clear separation between reasoning and answering modes within the residual stream. The figure below shows four representative projections along the difference-in-means vector. We observe the greatest cross-subject variation in the final layer, which is expected since the post-MLP residual stream at this layer feeds nearly directly into the unembedding layer and should therefore be highly subject-specific.

Transition plots across subjects

As in the main text, for each subject, we additionally computed the transition of the projection of the residual stream along the difference-in-mean vector across the </think> token.

To use a single vector of comparison, we compute the difference-in-means across all MMLU subjects $\hat{\delta}^l_{tot}$, and project each subject’s residual stream values (post-MLP) along this direction. In the figure below we plot the mean projections for MMLU Miscellaneous, MMLU College Physics, and the average over all MMLU subjects. In each, a sharp boundary can be found immediately at the </think> token position.

</think> token.Immediate answer template

To study the key mechanisms toggling these two output modes, we aim to minimize contextual differences during reasoning and answering. To this end, we exploit a documented behavior of DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Llama-8B characterized by the model entirely bypassing reasoning. Specifically, given prompts of the form:

<|User|>[MESSAGE]<|Assistant|>

the model will occasionally produce an empty reasoning region:

<|User|>[MESSAGE]<|Assistant|><think>\n\n</think>

before continuing to an answer.

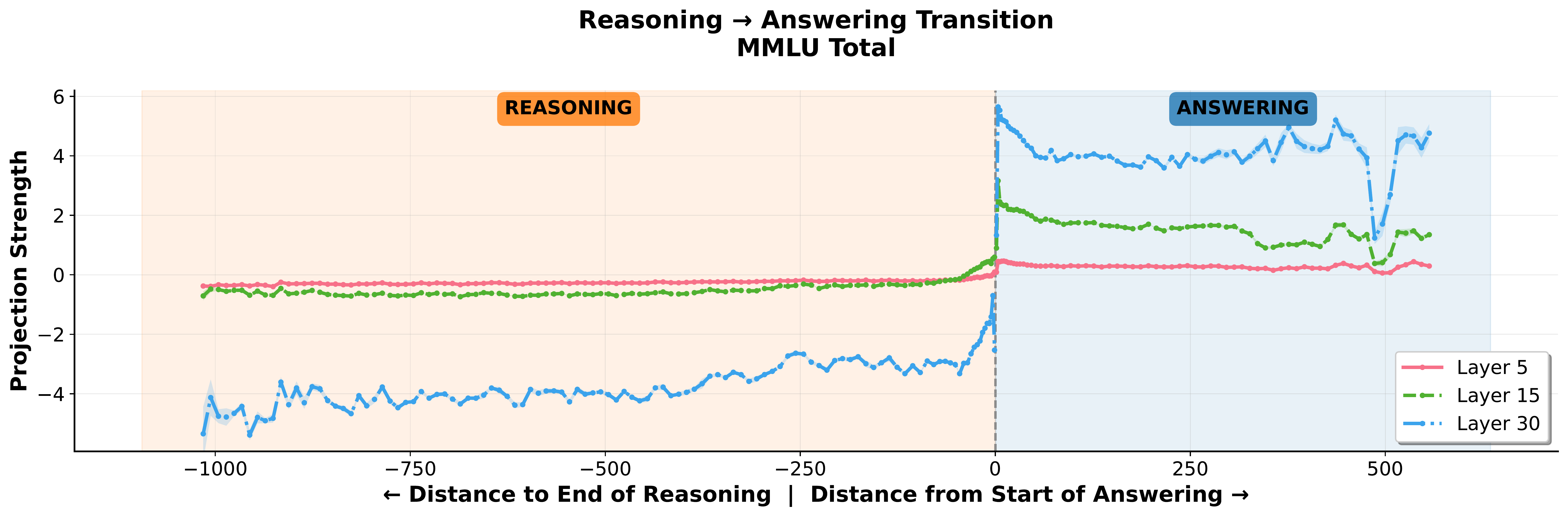

We use this pattern as our answering template. This is ideal as it (1) triggers answering mode immediately, (2) uses in-distribution behavior, and (3) differs minimally from the base reasoning template (differing by only \n → \n\n</think>\n\n).

Reasoning template: <|User|>[PROMPT]<|Assistant|><think>\n

Answering template: <|User|>[PROMPT]<|Assistant|><think>\n\n</think>\n\n

To confirm the validity of this template for our current difference-in-means study, we replicate our analysis using 100 prompts sampled from GSM-8K and using an immediate-answer format to produce answer tokens. Reasoning tokens were produced using the basic template. The resulting difference-in-means demonstrated $0.86 \pm 0.05$ cosine similarities across layers.

Token-normalized control

The frequency of generated tokens differs between reasoning and answering modes. To control for possible token-specific biases in the residual stream that might explain the observed shift, we applied a token-normalization procedure. We first identified the set of tokens that appeared in both reasoning and answering data. For each token $t$ in this set and each layer $l$, we computed the mean residual vectors:

\[\mu_{\text{reason}}(t,l), \quad \mu_{\text{answer}}(t,l).\]We then defined the overall mean for each token

\[\mu(t,l) = \tfrac{1}{2}\Big(\mu_{\text{reason}}(t,l) + \mu_{\text{answer}}(t,l)\Big),\]and normalized each residual vector by subtracting its corresponding $\mu(t,l)$. This procedure removes systematic token-specific biases which shift the residual stream.

We applied token normalization to a sample of 100 GSM-8K prompts and compared the resulting difference-in-means with the raw values.

The token-normalized difference-in-means had an average similarity of $0.88 \pm 0.02$ with the raw difference-in-means, indicating strong agreement. We therefore conclude that the simple raw difference-in-means is sufficient for our experiments.

Mechanistic analysis of the reasoning–answering transition

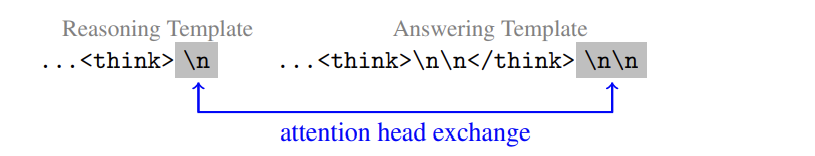

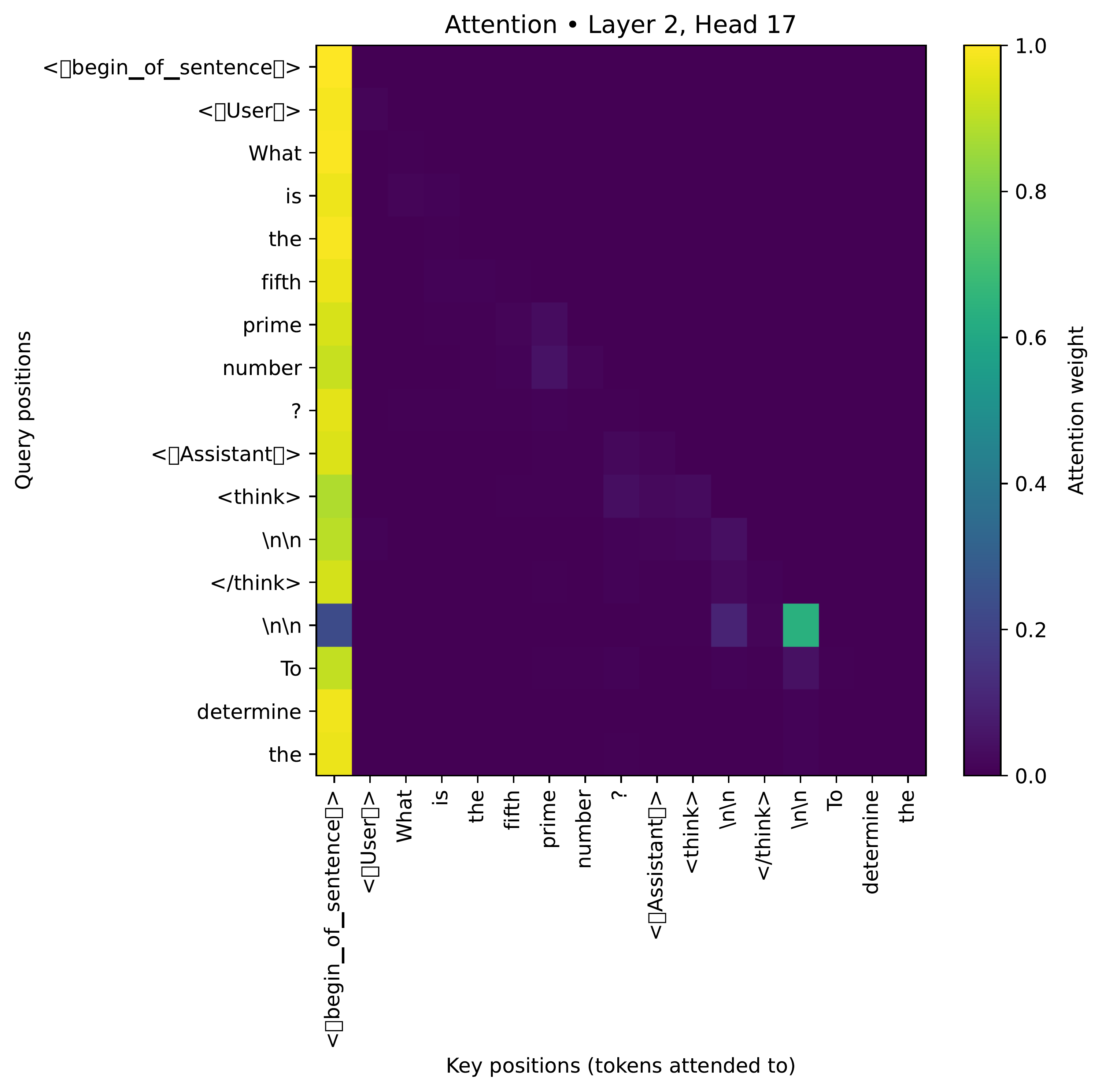

Attention-patching L2 shift analysis

To investigate the source of the observed residual stream shift, we performed attention head patching between our pair of templates (see the immediate answer template section above).

Using identical prompts, we exchange attention head outputs for each head between the reasoning template’s \n position into the reasoning template’s final \n\n position, and measure how individual heads contribute to the observed shift. Specifically, we measure the post-MLP residual stream shift at the final layer. Sweeping over all heads in the model produces a heatmap indicating each head’s impact. For short prompts, a single head controls the virtually the entire shift in the residual stream.

However, upon experimentation with longer prompts, this pattern in the attention patching heatmap vanishes. Further study is needed to understand the precise trigger connecting </think> to the onset of the residual stream shift.

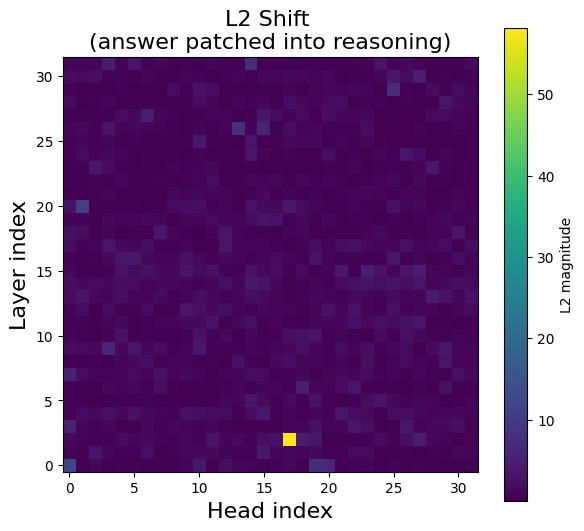

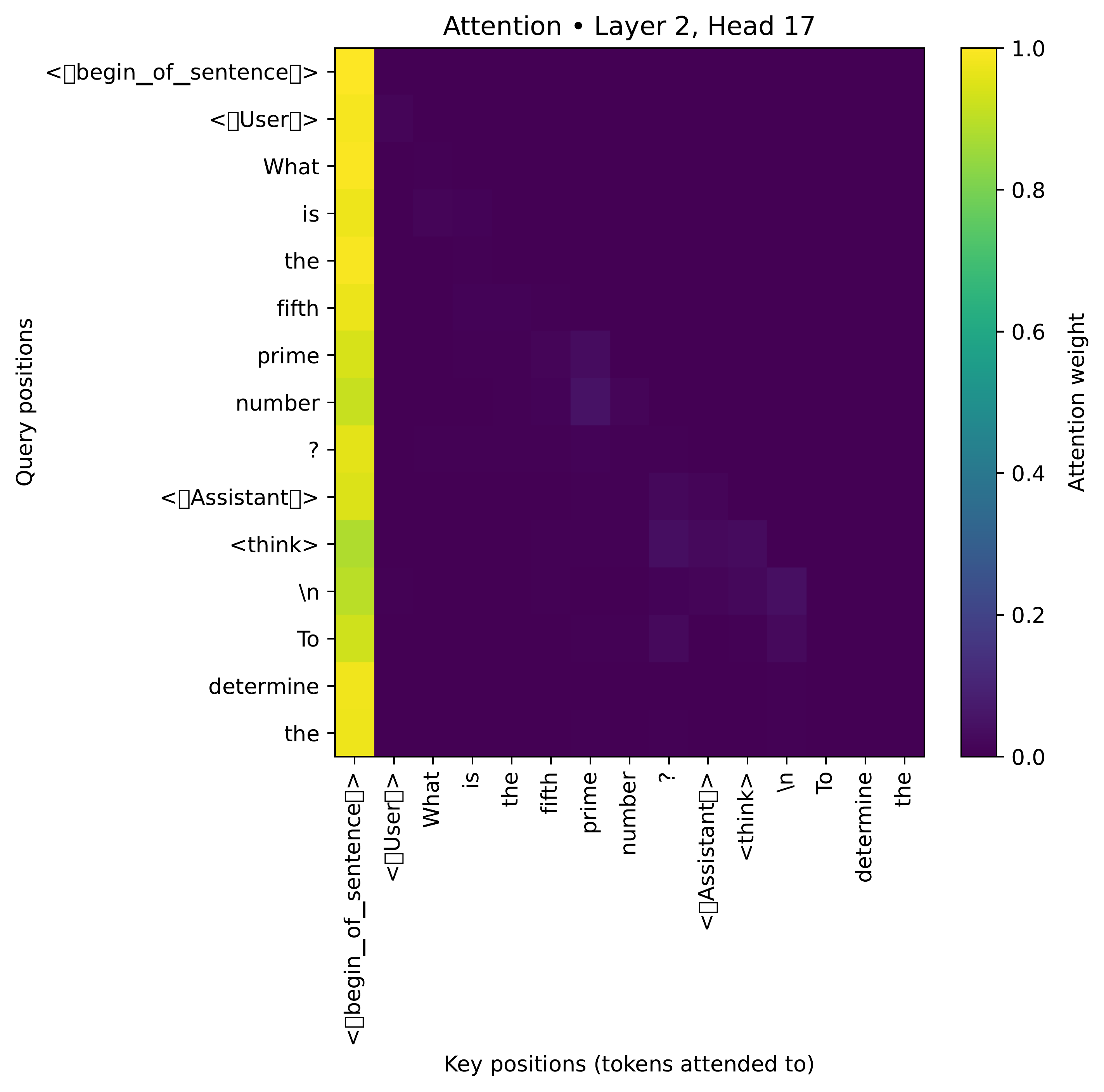

Mechanics of head (2, 17)

To probe the role of head (2, 17) within DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Llama-8B, we analyze its attention distribution during text generation. Using the standard reasoning template (terminated at EOS rather than </think>), we find that in experiments with short prompts, head (2, 17) either:

- Attends strongly to the BOS token, or

- If at the

\n\ntoken following</think>(which always precedes another\n\n), attends strongly to this\n\ntoken itself.

\n\n token following </think>, to that token.Controlling reasoning and answering via targeted interventions

Minimal injection via head (2, 17) vectors

Since the BOS token’s residual stream is prompt-independent, it suggests a minimal, prompt-invariant methodology for forcing the model into reasoning or answering mode.

Construct:

- A reason vector by applying head (2, 17)’s OV matrix to the BOS token’s resid_pre at layer 2.

- An answer vector by applying head (2, 17)’s OV matrix to the

\n\ntoken’s resid_pre at layer 2.

Though this does show promise within small prompts, longer prompts do not seem to respond to this intervention.