Suppose you’re at a restaurant, you have to pee, and you’re waiting at the bathroom door. It’s been 5 minutes since the last person entered, and as you wait you start to construct a mental model of what the fuck that guy in there could possibly be doing. And using that model, you try to calculate the answer to the question:

“How much longer do I have to wait?”

5 minutes

After 5 minutes, you’re running low on patience. Most people try to minimize the amount of time they spend in a public restroom, so this guy must really be going through something in there. This, you reason, is probably not going to be a short visit for him. You put the estimate for how much longer you have to wait at ~2.5 more minutes.

10 minutes

By 10 minutes, you’re exasperated. Your model for what is happening in that bathroom is starting to involve medical terminology. Is a catheter involved? Some sort of bag? You don’t want to think too hard about it, but now your time estimate for time remaining to wait increases to 5 more minutes.

20 minutes

By 20 minutes, you think, “There’s no way something normal is happening in there. This is definitely a medical event – something like food-poisoning”. You’ll be lucky if this guy’s out in the next 10 minutes.

60 minutes

It’s been an hour, you’ve told the staff, and now they’re running around trying to find the key to unlock the bathroom door from the outside. You imagine this fucking guy laying on the floor in there with some kind of foaming spittle pouring out of his mouth. Maybe an ambulance will be called (how long does that take?), meanwhile somebody’s going to have to do mouth to mouth – and you bet it’s gunna have to be you, because you’re the one who told everybody about this guy, and you took that CPR class once – and you know you won’t be allowed to say “no” because you’re grossed out by the weird foamy spit. Meanwhile, the chest compressions will for sure be done inside the bathroom where they’re gunna find the guy - nobody’s gunna care that you have to had to piss for well over an hour. Then it’s gunna be all weird to pee in there if he just died.

Best case scenario, you get to finally pee in 30 minutes.

Back at home

But at the end of the night, you’re back home. And once the adrenaline has worn off, and you’ve mouthwashed 11 times, and you’ve googled every permutation of the words “deadly weird foamy spit contagious”, you start to think about the pattern of those time estimates. At first it was 2.5 minutes, but as the amount of time you already waited increased, your estimate of the remaining time grew proportionally:

| Time Waited (minutes) | Remaining Time Estimate (minutes) |

|---|---|

| 5 | 2.5 |

| 10 | 5 |

| 20 | 10 |

| 60 | 30 |

Or, mathematically: \(\langle t \rangle_\tau = \gamma \tau\) Where

- $t$ is the remaining time left to pee

- $\tau$ is the time you’ve already waited

- $\gamma$ is a factor of proportionality

- and $\langle t \rangle_\tau$ is the expected remaining time after you’ve already waited a time $t$.

In words, this equation says

The expected amount of time you have to wait is proportional to the amount of time you already have waited

People understand this kind of relationship intuitively – no sane person, after waiting for an hour, would think to themselves “he’s probably just gunna need a couple more minutes”.

But how can we understand mathematically what we already know intuitively? Let’s reexpress that equation in terms of a probability distribution of time spent in the bathroom, and try to nail down what its implications are.

Mathematical Bathroom Implications

Define the probability distribution function (pdf) of the time a random person spends on a random trip to the bathroom:

\[p(T) \equiv \text{probability distribution of total-bathroom-trip-duration}\]If I have waited for a time $\tau$, what’s the pdf for the amount of time $t$ I have left to wait? This can be written:

\[p_{wait}(t | \tau) = \frac{p(t+\tau)}{\int_\tau^{\infty} dT p(T)}\]Let’s now plug these formulas into our relationship and see what happens:

\[\langle t \rangle_\tau = \gamma \tau\] \[\int_0^\infty dt \, t \, p_{wait}(t | \tau) = \gamma \tau\]note that

\[\int_0^\infty dt \, t \, p_{wait}(t | \tau) = \frac{\int_0^\infty dt \, t \, p(t+\tau)}{\int_\tau^{\infty} dT p(T)} = \frac{\int_\tau^\infty dT (T-\tau) p(T)}{\int_\tau^{\infty} dT p(T)}\]So that we now have the relationship

\[\frac{\int_\tau^\infty dT (T-\tau) p(T)}{\int_\tau^{\infty} dT p(T)} = \gamma \tau\]How does this help us? Well, we can take derivatives with respect to $\tau$, and see what constraints we get. First use the fundamental theorem of calculus on the numerator to write

\[\frac{d}{d \tau} \int_\tau^\infty dT \, (T-\tau) p(T) = -\left((T-\tau) p(T)\right)|_{T=\tau} \left( \frac{d}{d\tau} \tau \right) + \int_\tau^\infty dT \frac{d}{d \tau} (T-\tau) p(T)\]The first term vanishes, and the second term is a simple derivative, leaving us with

\[\frac{d}{d \tau} \int_\tau^\infty dT (T-\tau) p(T) = - \int_\tau^\infty dT p(T)\]But if you look at that original fraction, this matches the denominator (aside from the minus sign). That means we can define

\[F(\tau) \equiv \int_\tau^\infty dT \, (T-\tau) p(T)\]and write (adding the minus sign)

\[\frac{F(\tau)}{F'(\tau)} = -\gamma \tau\]This is a very simple differential equation, with the solution (found by integration) of

\[F(\tau) = C \tau^{-1/\gamma}\]So how does this help us? Well notice that if we take another derivative of $F(\tau)$, we get

\[F''(\tau) = - \frac{d}{d \tau} \int_\tau^\infty dT p(T) = p(\tau)\]And so we can say that

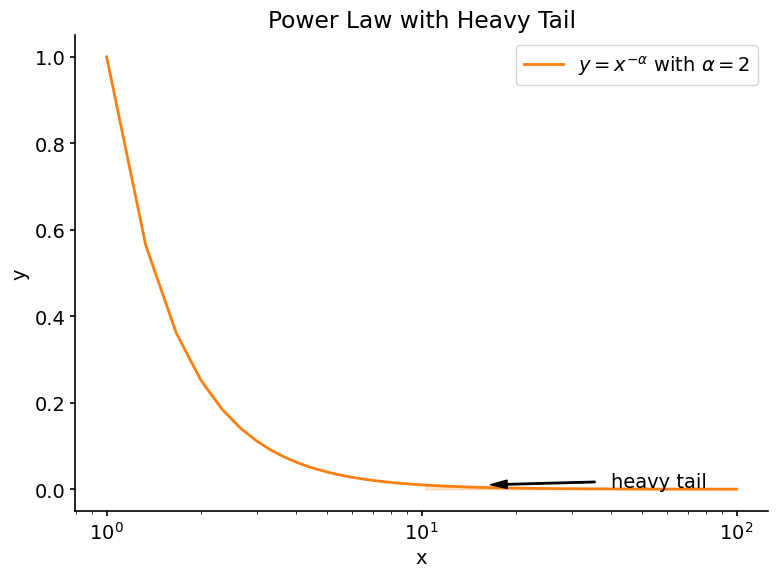

\[p(\tau) = F''(\tau) = \frac{d^2}{d \tau^2} C \tau^{-1/\gamma} = \frac{C}{\gamma}\left(1+\frac{1}{\gamma}\right) \tau^{-2 - \frac{1}{\gamma}}\]We want to normalize this, and since it’s a power law, we need to introduce a minimum time cutoff to do that (otherwise the integral blows up). This leaves us with the solution:

\[p(T) = \begin{cases} \displaystyle \Bigl(1 + \frac{1}{\gamma}\Bigr)\, T_{\min}^{\,1 + \frac{1}{\gamma}}\, T^{-\bigl(2 + \frac{1}{\gamma}\bigr)}, & \text{for } T \geq \tau_{\min}, \\[12pt] 0, & \text{for } T < T_{\min}. \end{cases}\]I love finding these kinds of things – complete mathematical equivalences between how a random guy waiting for the bathroom would describe things, and how anyone with a quantitative degree would describe the same relationship.

Regimes of Optimism / Pessimism

Looking at our first equation:

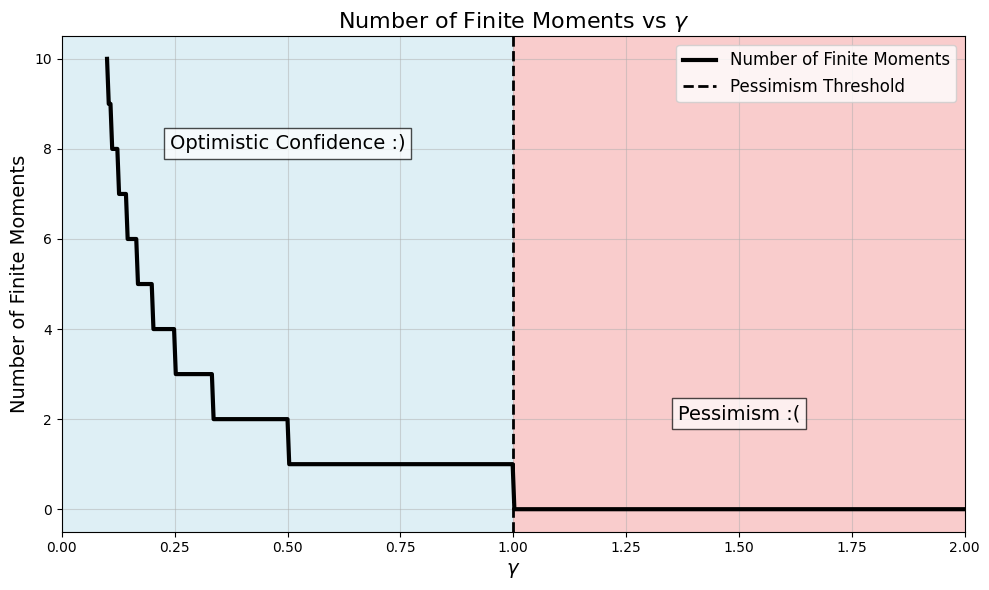

\[\langle t \rangle_\tau = \gamma \tau\]we can see that different values for $\gamma$ describe different degrees of optimism or pessimism. The larger the value of $\gamma$, the longer your waiting-time prediction gets. But now we can characterize that degree of pessimism with rigorous mathematical precision.

By integrating, we can compute each moment of this distribution (the $n^{th}$ moment of a distribution is defined as $\langle T^n \rangle$). Once we go through the math we find that the $n^{th}$ moment only exists when $\gamma < \frac{1}{n-1}$. When this is the case, it has the value,

\[\langle T^n \rangle = \frac{\left(1 + \frac{1}{\gamma}\right) T_{\min}^n}{\left(1 + \frac{1}{\gamma}\right) - n}\]

Each moment describes some degree of fluctuation in an estimate about the time a bathroom trip will take. A moment not existing (being infinite) is a reflection of how much variability there is in $p(T)$. Roughly, when moments are infinite, the distribution is said to have a heavy tail.

What does this mean?

Well, the smaller $\gamma$ is, the more moments exist, and the more optimistic we are. Small $\gamma$ means you think you have a pretty good grasp on how long you might be waiting.

But if $\gamma \geq 1$, this math means your level of pessimism is basically catastrophic. You might be able to tell somebody how much time you think you have left to wait before you pee, but if they ask about your uncertainty in that estimate, you’d burst into tears, because the variance is infinite.

When power laws have an exponent of 2, they’re at a self-similar critical point. We can see this self-similarity that people talk about because for us it corresponds to $\gamma=\infty$. Regardless of how much time has elapsed, you think you’ll have to wait the same amount longer (an infinite amount of remaining time).

Exponential Side-note

If \(\langle t \rangle_\tau = \gamma \tau\) gives us a power law, what would we get with:

\[\langle t \rangle_\tau = \Delta\]Well, this is the statement of

No matter how much time has passed, the expected remaining time is the same

In other words, this is memorylessness, and we are instantly left with only one distribution that gives us this: the exponential distribution:

\[p_{exp}(T) = \Delta^{-1} e^{-T/\Delta}\]Party-pooper Rebuttal / Stop-being-so-literal-and-just-enjoy-life Response

At this point you might be saying,

“uh, okay cool math Steve, but I’m pretty sure that whenever I’m waiting for a bathroom to open up, it does in a couple of minutes, and nobody has ever died in one while I was waiting.”

You know what, you’re probably right. This entire argument probably only has any validity in the extreme tails. But for the sake of this blog post, and for the sake of having fun, let’s pretend that it is basically accurate.

But then you might follow up with something like this

“But Steve, every time I use the bathroom, the time I’m going to spend in there is very predictable – something I could characterize with a typical-value estimate, $t_0$ – not really true for power laws. Also, I’m pretty sure this is true of everyone. How are you getting a power law out of a combination of a bunch of exponentials?”

Let’s try to address this: if nobody’s individual bathroom duration distribution has a heavy tail (each person’s individual trip to the bathroom could be very well-characterized by a typical time $t_0$), then how could the combined bathroom duration pdf, $p(T)$ have one?

We’ll say that each bathroom trip has a duration pdf described by an exponential with a characteristic time $t_0$. (Note that we really only care about the tails, here so I’m saying people spend an exponential distribution of time in the bathroom, even though of course the plurality of time spent in the bathroom is not 0 seconds).

Again, let’s write down what this would mean mathematically if we expect some probabilistic combination of $t_0$’s to give us our $p(T)$:

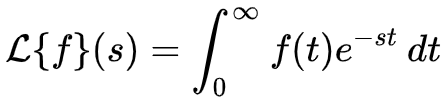

\[\int_0^\infty dt_0 \ t_0^{-1}e^{-T/t_0} \rho(t_0) = p(T)\]Above, $\rho(t_0)$ is a probability distribution of characteristic times, and $t_0^{-1}e^{-T/t_0}$ is each exponential distribution contribution. A solution for $\rho(t_0)$ within this equation would mean that even though each individual bathroom duration is exponential, the total bathroom duration is a power law.

It turns out that what I wrote above has a name, it’s the laplace transform of $\rho(t_0)$.

Therefore we can apply the inverse Laplace transform to the power law $p(T)$, and get our solution:

\[\rho(t_{0}) \;=\; \Bigl(1 + \frac{1}{\gamma}\Bigr)\; T_{\min}^{\,\bigl(1 + \tfrac{1}{\gamma}\bigr)}\, t_{0}^{\,\bigl(1 - \tfrac{1}{\gamma}\bigr)}\; \Gamma\!\Bigl(-\bigl(1 + \tfrac{1}{\gamma}\bigr),\,\frac{T_{\min}}{t_{0}}\Bigr) \quad \text{for } t_{0} > 0.\]where we used the “upper incomplete” gamma function

\[\Gamma(a, z) = \int_z^\infty t^{a-1} e^{-t} dt\](don’t worry, I had never heard of the “upper incomplete” version of the gamma function either).

What this is saying then, is that a bunch of exponentials, with their characteristic times distributed in a power law way, gives us a power law distribution in time.

Every trip to the bathroom has a characteristic time it’s going to take. It’s the distribution of types of trips to the bathroom that gives us the power law.

Remember that this is essentially what our imagined person waiting for the bathroom was intuitively doing. As time went by, he was excluding more and more scenarios, each of which had a typical duration which was much shorter than the time he’s already waited. By the time an hour went by, there were only the most rare explanations with a sufficiently long $t_0$ that were still possible; namely that the guy died or had decided to start living inside the bathroom.

I plan on writing more about power laws, because they pop up in a bunch of interesting places. Hopefully you think about them next time you’re waiting for the bathroom.