With the assassination of the CEO of UnitedHealth, a lot of people are expressing online that health insurance is a scam – they pay into their health insurance every month, and yet they seem to never get any of that money back.

I want to really quickly sketch out why this is actually completely consistent with insurance operating correctly.

Benevolent Health Insurance Incorporated (BenHealth)

To show that the “insurance is a scam” feeling is kind of inevitable, let’s first invent a perfect health insurance company, which I’m titling “Benevolent Health Insurance Incorporated”, or “BenHealth” after its corporate rebrand.

BenHealth is the best possible insurance company out there. No customer gets charged more because of some feature about them. There is no discrimination based on age or preexisting conditions. Everyone is charged the same amount.

This perfect insurance company is actually so perfect that it doesn’t even take a profit. Every single employee of this company works for free, it passes on no building-maintenance costs to its customers, no AWS fees, nothing. This place is entirely operated and run by benevolent healthcare-savvy monks sworn to poverty.

Each customer of this insurance company pays the same yearly fee of $C$, and in exchange they receive coverage for the random charges that might arise during the year. Let’s say these charges are a random variable, $x$, potentially a different value each year. Because the healthcare company takes no profit, we can say the following:

\[C = \langle x \rangle\]That is, insurance costs per person are exactly the same as the total amount the company paid out, divided by the number of people – which equals the average payout, $\langle x \rangle$. (For simplicity, we’ll assume there are infinitely many customers.)

A Tiny Bit of Approximate Reality

Many healthcare costs obey a sort of Pareto principle – where the small top fraction of people make up a large fraction of the overall costs. For example, this article claims the top 20% most expensive people made up 85% of the healthcare costs. Let’s say this is true of the healthcare model we’re describing.

To get quantitative, let’s define the following

-

$f$: The top fraction of the population we’re considering. (Top 20% means $f=.2$.)

-

$r$: The fraction of costs which go to this group. (85% of costs means $r=.85$.)

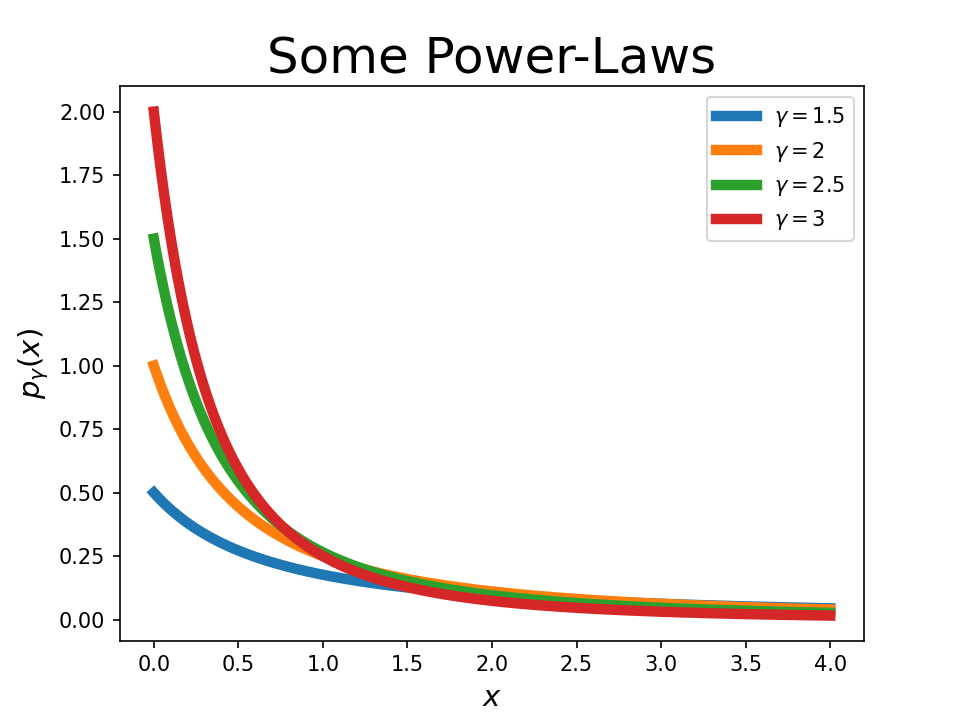

It turns out that what we’ve written above is satisfied (not exclusively) by a power-law:

\[p(x) = \alpha (x+\beta)^{-\gamma}\]

Power laws tend to pop up when the extremes of a distribution make a disproportionate impact on the total. In words, this equation might mean that if we look at everyone receiving any healthcare care, the top 10% most expensive people account for a disproportionate fraction of the expenses – maybe these are people who are currently in the hospital for multiple days. Now, of these people in the hospital, the top 5% (say, people in the ICU) again account for a disproportionate fraction of their costs, and onward.

Math (feel free to skip)

Now let’s set $\alpha$, $\beta$, and $\gamma$ to make mathematical sense, and match the $f$, $r$ pareto rule we’ve defined:

First, normalizing so that $p(x)$ is a probability distribution:

\[1 = \int_0^\infty \alpha (x+\beta)^{-\gamma} dx = \frac{\alpha (x+\beta)^{1-\gamma}}{1-\gamma} |_0^{\infty}\]this gives us a constraint on $\alpha$, meaning

\[p(x) = \frac{\gamma-1}{\beta^{1-\gamma}} (x+\beta)^{-\gamma}\]Here we’re assuming $\gamma>1$ so that things converge. Additionally, we want this thing to not be too weird – e.g. the distribution of healthcare costs should have a mean. This constrains $\gamma>2$.

Now to force our Pareto principle to be true, let’s compute the top fraction $f$ of individuals in any group of most expensive people, and how much they cost as a fraction of the group.

The fraction of individuals costing more than $x^*$ is:

\[\int_{x^*}^\infty \frac{\gamma-1}{\beta^{1-\gamma}} (x+\beta)^{-\gamma} dx = \left( \frac{1}{1+x^* / \beta}\right)^{\gamma-1}\](Remember $\gamma>2$ and $\beta>0$.)

In other words, (inverting) the top $f$ most expensive individuals begin at $x^*=\beta (f^{\frac{1}{1-\gamma}} -1)$.

Next, let’s compute the total cost of those individuals in the top $f$ fraction of the population. Note that we’ve been using a probability distribution for costs of individuals in the population, $p(x)$ where $\int p(x) dx=1$. If we want to work with the total cost of everyone, we’d multiply this by $N$, the number of customers:

\[N \int_{x^*}^\infty \frac{\gamma-1}{\beta^{1-\gamma}} (x+\beta)^{-\gamma} x dx\]This becomes

\[N \frac{\gamma-1}{\beta^{1-\gamma}} \left( \frac{\beta (x^* + \beta)^{1-\gamma}}{1-\gamma} - \frac{(x^* +\beta)^{2-\gamma}}{2-\gamma}\right)\]We know what $x^*$ is in terms of $f$ – the fraction of top individuals, so we can plug in to obtain the expected total cost of healthcare customers in the top $f$ fraction of cost – which im calling $\text{CostTop}(f)$:

\[\text{CostTop}(f) =N f \beta \left(\frac{\gamma-1}{\gamma-2} f^{\frac{1}{1-\gamma}} -1\right)\]So far we just have equations, let’s connect these with our Pareto principle. Out of all individuals (top fraction $=1$), the total cost of the top $f$ should make up a fraction $r$.

In an equation:

\[\text{CostTop}(f) / \text{CostTop}(1)= r\]What constraint do we get here? Well if we simplify our equation, $N$ and $\beta$ fall out, and we get

\[f \left((\gamma-1) f^{\frac{1}{1-\gamma}} - (\gamma-2)\right) = r\]We can numerically solve this for $\gamma$, setting $\beta=1$ since it’s an overall scaling constant.

Now that we have our constraints, we can make a nice little power-law model for our healthcare costs, and move on to look at BenHealth’s inevitably glowing customer satisfaction surveys.

Customer Satisfaction

At BenHealth, your experience is important to us. We have our somewhat realistic distribution of healthcare costs in this model universe, where the top $f$ of expensive patients take up a fraction $r$ of the resources. Now let’s look at how much things cost for the customers.

Let’s first look at which customers break even each year. For them, healthcare costs were less than the cost of treatment they received in that year. These people will surely feel that they have not been scammed, since they actually gained over the course of the year from their health insurance.

To break even, the mean healthcare cost (the amount you paid) must be lower than your healthcare costs that year. For what fraction of the population does this occur?

We know that the cutoff of the top $\phi$ expensive customers (they’re at the $100\times (1-\phi)$ percentile of expenses) starts at

$

x^*=\beta (\phi^{\frac{1}{1-\gamma}} -1)

$, so we can write:

We also know that $\int_0^\infty p(x) x dx = \beta / (\gamma-2)$, so we can plug in our parameters and solve for $\phi$:

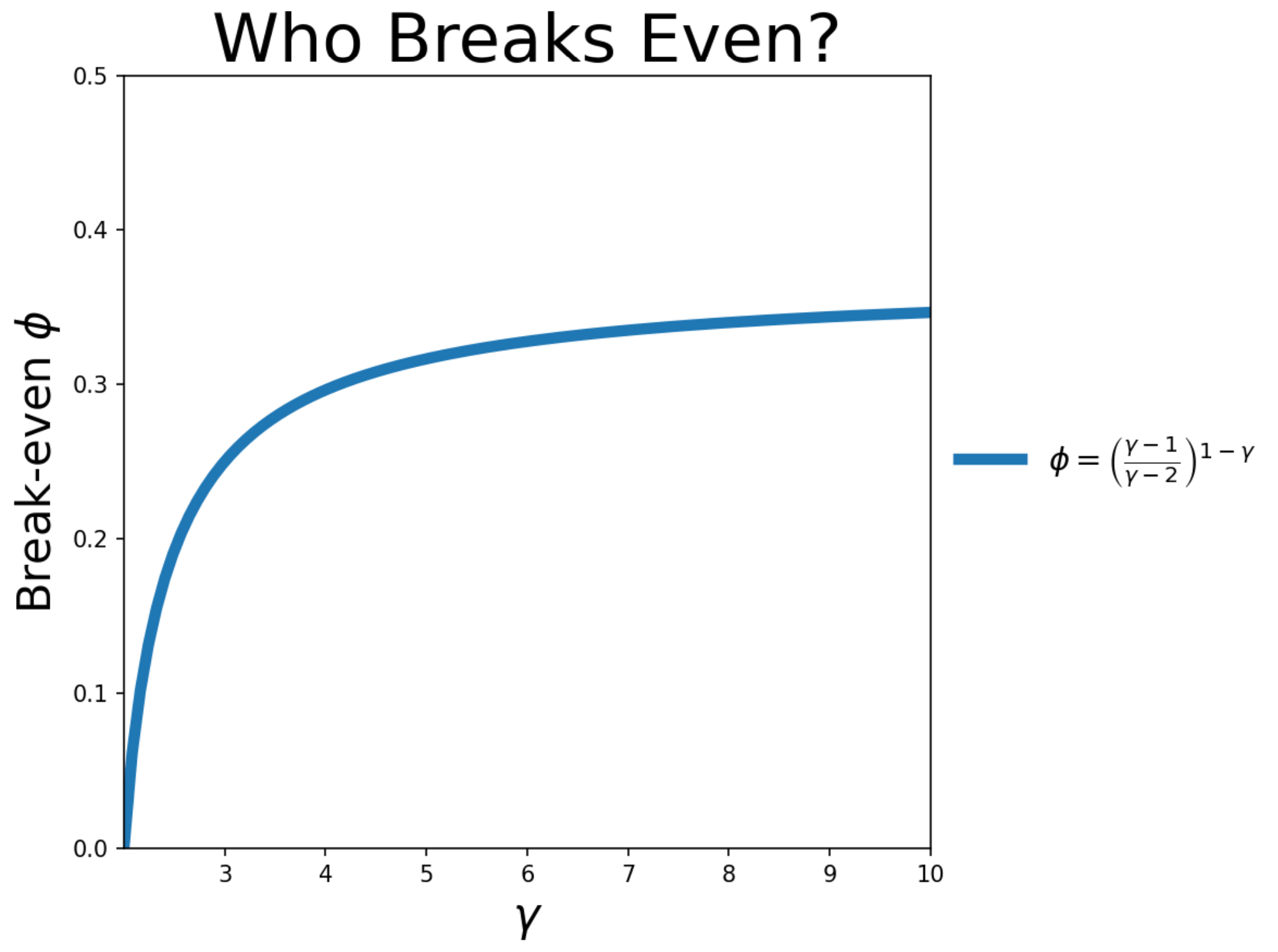

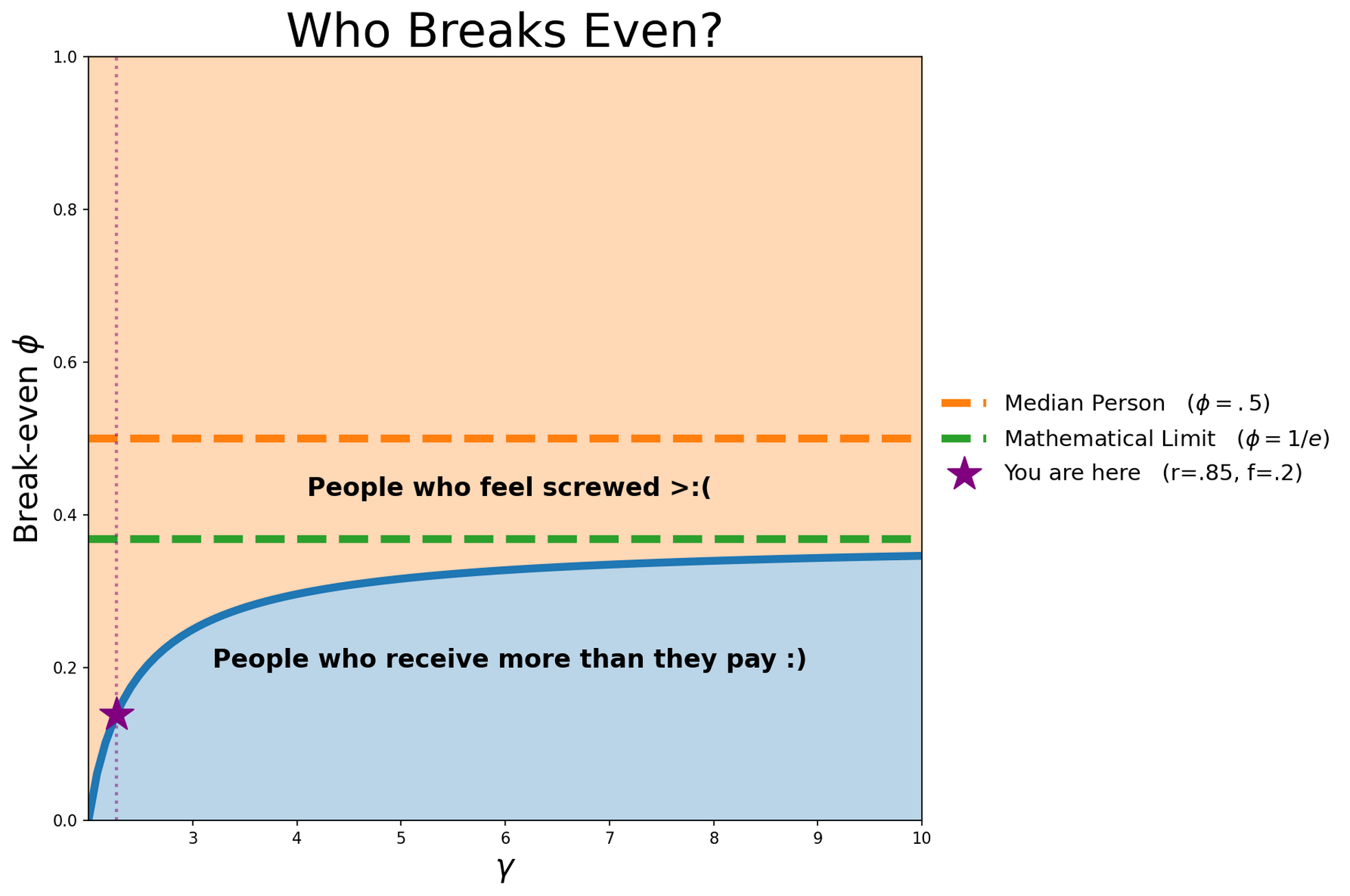

\[\frac{\beta}{\gamma-2}= \beta (\phi^{\frac{1}{1-\gamma}} -1) \implies \phi = \left(\frac{\gamma-1}{\gamma-2}\right)^{1-\gamma}\]Okay so let’s talk numbers, where is this break-even-point? Who doesn’t feel scammed in a given year?

Plugging in numbers

What are $r$ and $f$? – well let’s say healthcare costs follow the 80/20 rule (Most resources seem to say it’s worse than this). 80% of costs come from the top 20% of patients, and so $r=.8$ (80% becomes the fraction .8), and $f=.2$ (the top 20% becomes $.2$)

Plugging this in gives us $\phi \approx .18$. This means you need to be in the top 18 percentile of expenses to not lose money each year. If we use numbers ($r=.85$, $f=.2$) from an actual study, we get $\phi \approx .14$.

What does the Pareto rule have to be for a median person to break even? Let’s look at the break-even fraction, $\phi$ (here, $\phi$ is the fraction of people whose healthcare costs more than you):

\[\phi = \left(\frac{\gamma-1}{\gamma-2}\right)^{1-\gamma}\]This function grows with $\gamma$ (see plot below)

So how large can it get?

\[\left(\frac{\gamma-1}{\gamma-2}\right)^{1-\gamma} = \left(1 + \frac{1}{\gamma-2}\right)^{1-\gamma}\]Taking $\gamma$ to infinity gives us

\[\lim_{\gamma \rightarrow \infty} \left(1 + \frac{1}{\gamma-2}\right)^{1-\gamma} = \lim_{\gamma \rightarrow \infty} \left(1 + \frac{1}{\gamma}\right)^{-\gamma} = 1/e \approx 0.37 < .5\]

Simply put, you will never be in a situation in which the median person is getting back what they pay in during a given year. This isn’t some quirk of power laws either – in any world where the healthier 50% of people receive less care than the sicker 50%, it is mathematically impossible, even if you had BenHealth.

How long until I get my money back??

“Sure,” you might say, “but I’m fine not getting my money back over the course of a year. I’m pissed because I haven’t got my money back over the course of many years.”

Well first of all, are you young? Because if so, you’re probably paying for old people. Hopefully you get to become an old person one day. But let’s ignore that.

Let’s just pretend everyone is the same person. Let’s even assume there is zero correlation between the percentile of your health costs from one year to another.

Okay, how long until I make my money back?

Well, again, you probably will not.

The median BenHealth customer will not make their money back in healthcare over any timespan.

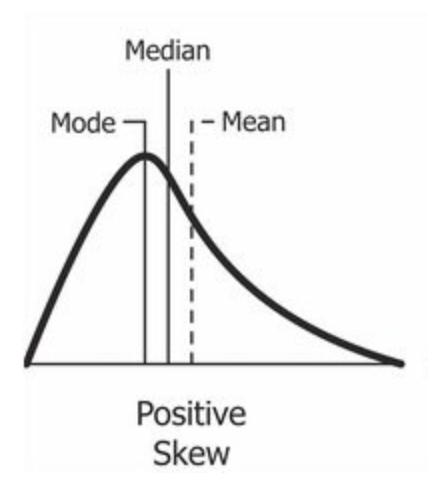

Why is this? Well, one year’s health costs were a power law, totally left-skewed. The skew-ness of a distribution tells us that the mean value is always greater than the median.

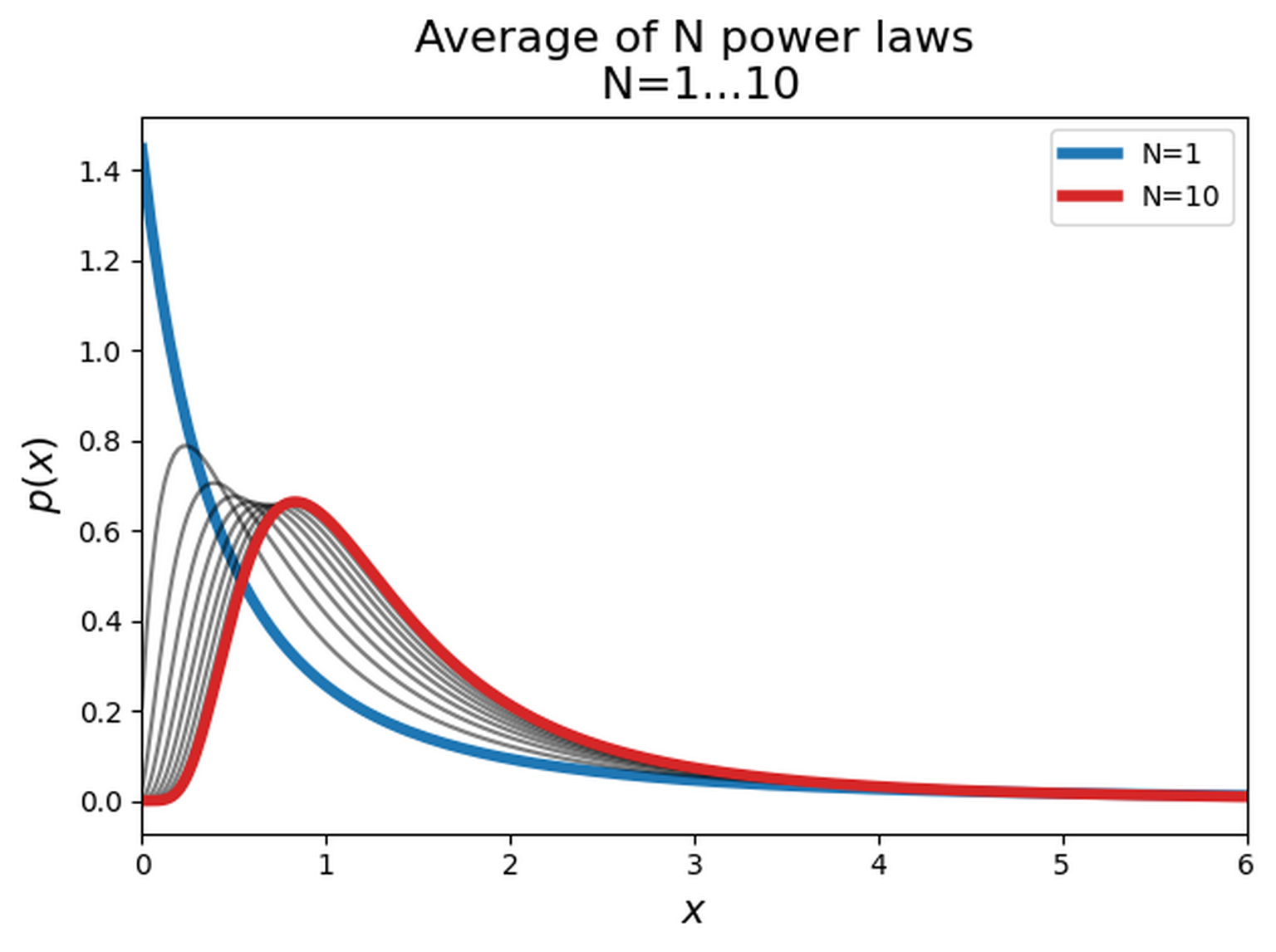

What about multiple years of costs? Well the actual distribution that this produces is pretty complex (you have to convolve together N power laws). If you’re willing to wait for infinity, ($N \rightarrow \infty$) the sum of power laws converges to a gaussian, with zero skew and mean $N \times \text{Average Yearly Healthcare Price}$. But for any number of years less than infinity, the sum of costs is always positively skewed, meaning the mean value is always greater than the median, and most people always end up paying more for healthcare than they get back.

This is Insurance

Something’s definitely gone wrong right? This tells us that even though our insurance company was the opposite of evil, a large fraction of customers are still liable to feel scammed.

This is, however, how all insurance works. Generally speaking, insurance of all kinds is there to cover you for tail-risks – events and circumstances that no person can reasonably be expected to suddenly pay for. These tail risks might not happen to you in a decade (hopefully) let-alone a year. We have health insurance for the same reason cops wear body armor. But a lot of people see it as more akin to a gym membership.

Does it even make sense to expect insurance to cover the relatively small, non-life-threatening, predictable medical expenses that we encounter? I don’t know. Maybe if we only expected insurance to kick in when something truly horrible happens, people wouldn’t feel so scammed? (But I have no idea).

Of course it’s still totally possible for a health insurance company to be totally evil – to lie about what it covers, mislead patients, and not pay out when they had promised to. But what does seem to be true is that even in our fictional perfect universe, people are bound to think that BenHealth is a scam. Hopefully nobody kills the CEO.